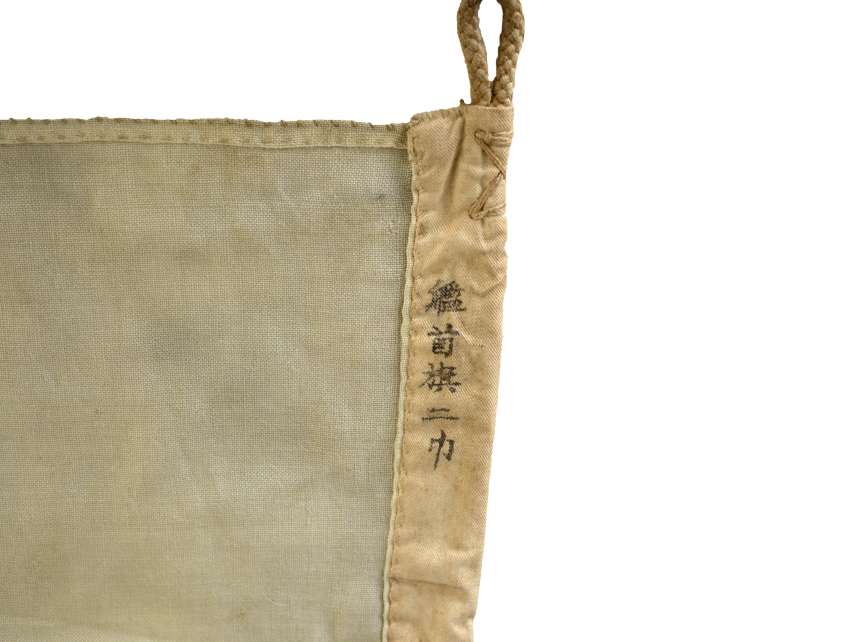

This Japanese flag was taken from Japanese Ensign Kazuo Sakamaki when he was captured on the beach in Hawaii on 8 December 1941. Ensign Sakamaki piloted one of the five midget submarines that attacked Pearl Harbor and is the only one of the ten Japanese submariners to survive. He became “Prisoner No. 1,” the first Japanese POW in World War Two. He was interrogated, then shipped to a POW camp in Wisconsin, where he remained for the rest of the war. After the Japanese officially surrendered on 2 September 1945, Sakamaki and the other Japanese POWs were transported back to Japan, with varying reactions. Sakamaki himself received hateful messages either shaming him for not committing harikari or threatening to kill him for the dishonor he brought upon himself and his country. He survived the torrent of abuse and eventually became the president of the Toyota company in Brazil, and passed away in 1999 at the age of 81.

In 1991, Sakamaki visited the National Museum of the Pacific War and saw for the first time since 8 December 1941 the midget submarine he had piloted to Pearl Harbor, which remains to this day in the museum’s collection.