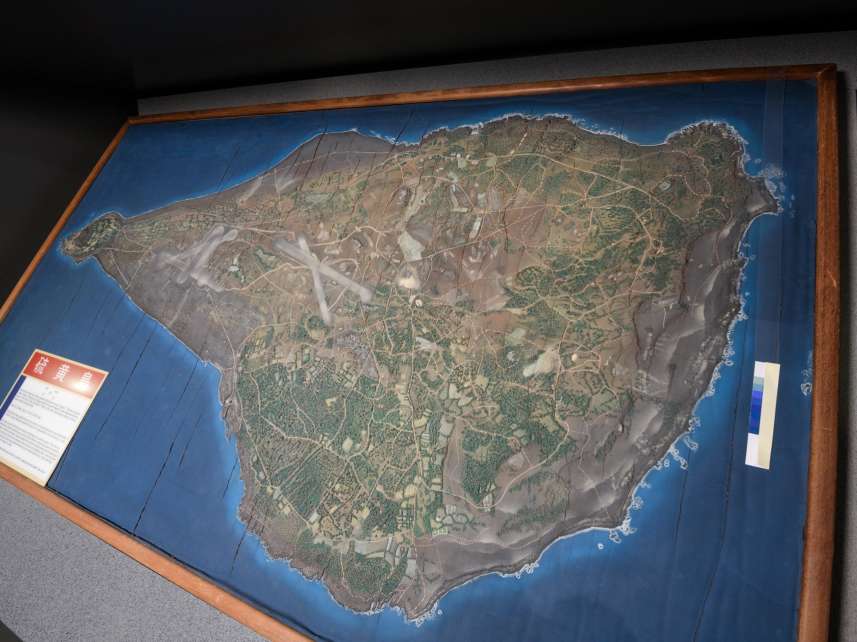

Three-dimensional foam rubber map of Iwo Jima: This map was constructed at the Terrain Model Workshop at Camp Bradford, Virginia, prior to the Iwo Jima invasion. Maps like these were fabricated using aerial reconnaissance photographs. They were intended as planning aids for pilots, gunners and infantry who would participate in the invasion of the island. In addition to its strategic importance, Iwo Jima was also a psychological target. Taking this island, which had been in Japanese possession for centuries, would be a major blow to Japanese morale and add to the pressure to surrender. The Americans planned to seize Iwo Jima and then Okinawa in rapid succession before moving on to the Japanese Home Islands. These plans were delayed by the struggle over Iwo, and after the battle for Okinawa, President Truman authorized the use of the atomic bomb rather than approving the invasion of the Japanese main islands.

This map was never sent to the fleet because it was discovered that the Japanese had begun construction on a third airstrip. Lt. Robert Laddish, the executive officer of the Workshop, kept this obsolete version as a souvenir.