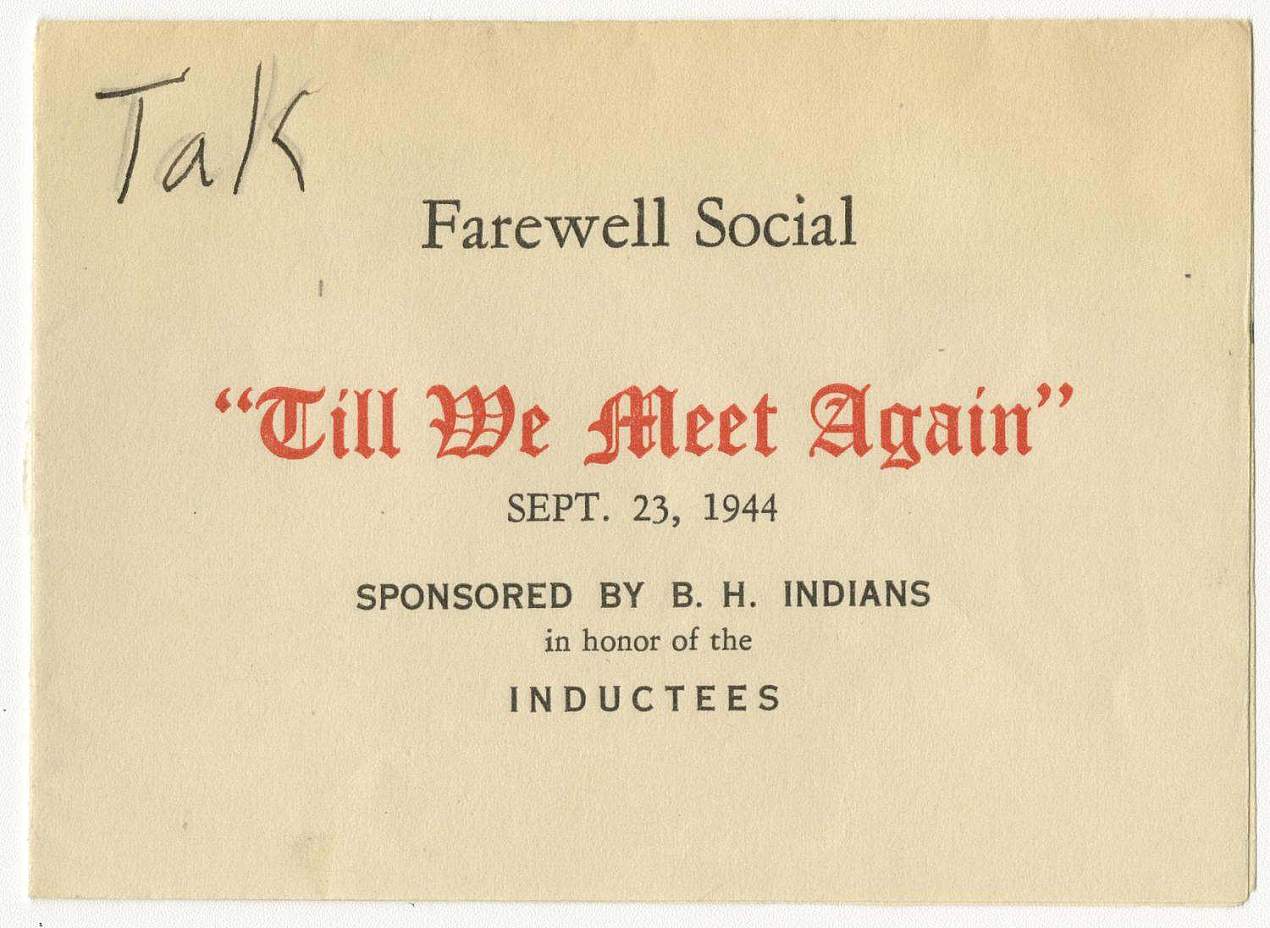

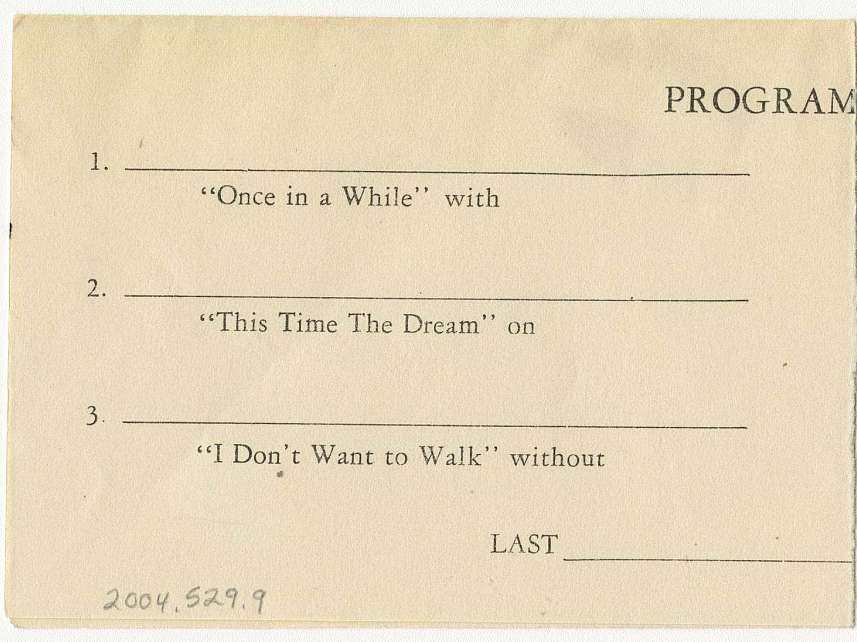

Takeo Shiroma’s dance card from the “Farewell Social” by the Boyle Heights Indians, a social group from Block 45 of the Poston Relocation Camp in Arizona. Takeo and his wife Roberta were both held at Poston as children when they and their families were relocated following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Roberta, whose father was Japanese and mother was American, recalls her time as a nine-year-old internee as “fun,” but described in an oral history for the National Museum of the Pacific War in 2003 that she also felt very anxious. Takeo and Roberta described their treatment at the camp as friendly, with freedom to visit other camps as long as they obtained a pass to do so. Takeo, whose parents were both from Okinawa, was allowed to leave the camp to work in an agricultural field in Utah later during the war due to the shortage of men. Neither Mr. nor Mrs. Shiroma recalled any ill treatment nor feelings of anger or resentment from their incarceration, but they admit that they would never see the same happen to any group of Americans again.

Click here to listen to the oral history interview with Takeo and Roberta Shiroma